Photo (source): The “Old Main” building of the hospital served as the Men’s Department.

Prior to the establishment of mental health facilities in the United States most individuals suffering from mental disorders were relegated to living as beggars in almshouses, being secluded in damp basements, or confined for the rest of their days in prison. Patients in asylums fared only slightly better, as they were often subject to questionable treatment at the hands of their physicians.

At the time conventional medical practitioners did not have the benefit of advanced imaging techniques, testing procedures, and psychiatric treatment breakthroughs we take for granted. Physicians in the 1800’s believed that forms of “insanity” were thought to all derive from either direct physical or indirect moral sources. Brain specimens from patients post mortem often revealed direct physical sources for insanity such as physical trauma, lesions, tumors, syphilis, or other organic causes. Indirect moral sources as a cause for insanity ranged a wide gamut from the entirely plausible to highly improbable. These factors could include fatigue, seduction, jealousy, religious excitement, drunkeness, tobacco use, drug addiction, masturbation, lack of education, and financial difficulty.

The government of Indiana’s official concern for individuals with psychological issues dates back to 1827. That year the state legislature allocated a small parcel of land known as “square 22” with a small log cabin in Indianapolis to be used as a “lunatic asylum.” In 1844 political activist Dorothea Dix persuaded the Indiana General Assembly to appropriate funds for an official state-run asylum. Governor Whitcomb appointed his associate Dr. John Evans as commissioner in charge of developing the hospital. In fall of 1845 the state purchased a 160-acre plot of farmland three miles from the center of Indianapolis from Nathaniel Bolton for the sum of $5,300.

Photo: A well worn workbench in the former power station.

To prepare for construction Dr. Evans travelled east to study mental institutions at his own expense. His subsequent building recommendation for the hospital followed the Kirkbride Plan. One defining element of Kirkbride Plan architecture is a central core with staggered wings. Each area had prescribed uses to maximize hospital efficacy. The core contained offices, reception room, visitor’s suite, kitchen, chapel, and other essential rooms. The wings were partitioned into wards accommodating patients according to their classification and gender. In addition to patient rooms, the Kirkbride Plan also allocated space for recreation, hygiene, food service and other hospital logistics. The grounds surrounding these types of buildings were quite expansive and ornate, thus guaranteeing a level of seclusion from an intruding and curious public.

In addition to architectural style requirements, the Kirkbride Plan is heavily ingrained with Moral Treatment philosophy. In combination with medical care patients were expected to participate in recuperative therapy, religious exercise, education courses, work therapy, social engagements, and a host of other activities perceived to have curative effects. Hospital staff were discouraged from using restraints whenever possible, refrain from using physical violence, show compassion to their wards and have a thorough understanding of their condition.

On May 5, 1846 construction of the Indiana State Hospital for the Insane broke ground. As time progressed a myriad of support structures sprawled across the expansive plot of land. These included expansions to the “Old Main” Men’s Department, the “Seven Steeples” Women’s Department, Central Boiler House and Plant, Carpenter’s Shop, Pathological Department, Kitchen, Dining Rooms, Greenhouse, Cold Storage, Upholstry Department, Amusement Hall, Chapel, Fire Department, staff homes, and Administration Building among others. The elegant architecture of the “Seven Steeples” Women’s Department was admired for its elegance, but in reality it possessed eight steeples.

The new facility opened its doors and welcomed five patients on November 21, 1848. Treating mental illness at that time involved a great deal of speculation with little hope for recovery for many patients. The hastening pace of industrialization, the ravages of the Civil War, and friction between Victorian era and American societal norms further compounded matters. As such the patient population at the hospital would greatly increase to the point where it suffered from chronic overcrowding.

Photo: Aged chairs succumbing to the elements in one of the many derelict hospital structures.

Ideally the ultimate goal of any hospital is to provide the best care it can for patients. In pursuit of this goal, however, the hospital was not able to avoid becoming a pawn for those with political or ideological agendas. In fact the hospital experienced regular intervals of discord both internally and publicly. Cyclical underfunding brought about by fiscal conservatism ensured that the hospital was consistently unable to perform some of its duties. Outrage directed towards the hospital in times of crisis were then typically followed by a period of progressive reform.

On the surface the hospital appeared to be quite progressive in its efforts to properly treat its wards. Behind the scenes, however, was a hidden reality for the most indigent and dangerous patients. In 1870 the Indiana Governor received the following report on some of the deplorable conditions at the hospital.

“…basement dungeons (are) dark, humid and foul, unfit for life of any kind, filled with maniacs who raved and howled like tortured beasts, for want of light, and air, and food, and ordinanry human associations and habiliments…”

Dr. Everts – Superintendent

Central State Hospital for the Insane

Declining conditions at the hospital also included lack of proper staff training, heat, proper lighting, ventilation, structural maintenance, proper bedding, and kitchens infested with cockroaches due to inadequate funding. Dr. Everts efforts to highlight the plight endured by the hospital fell on deaf ears, which led to his resignation in 1872.

It took the printed word of actual hospital patients who endured the conditions at the hospital to arouse public indignation. Civil war veteran and former patient Albert Thayer disseminated his accounts along with others via a broadside called “Indiana Crazy House” to churches, politicians, and Indiana citizens. Thayer’s efforts were somewhat successful in improving physical conditions at the hospital. Despite these improvements, primary caregivers at the hospital continued to be poorly trained medical attendants rather than actual physicians. Patient abuse at the hands of their overwhelmed caretakers continued unabated. The misuse of sedatives and physical restraints to ease the staff workload was common practice.

In late 1883 the hospital hired the first officially recognized female medical doctor in Indiana. At the time of her arrival Sarah Stockton was just one of only 22 female physicians in the United States. Dr. Stockton was tasked primarily with the care of female patients. Her focus centered on reproductive ailments, which were at that time generally thought to exacerbate mental illness.

Dr. Stockton’s hiring was just one of the calculated efforts by Superintendent Richard Fletcher to bring about reform. To protest the poor conditions at the hospital Fletcher caused a spectacle when he publicly burned the hospital’s physical restraints in a bonfire in 1885. Several other practical reforms were instituted under his tenure. Medicinal use of whiskey was reduced from three gallons per day down to just one pint. Patients enjoyed the benefit of free dental care. He also brought dignity to those patients who had passed on by abandoning the practice of anonymous burials.

Photo (source): 1931 aerial photo from the south looking north. Notice the two large staggered Kirkbride Plan buildings.

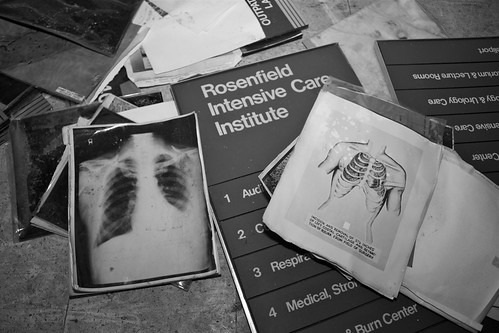

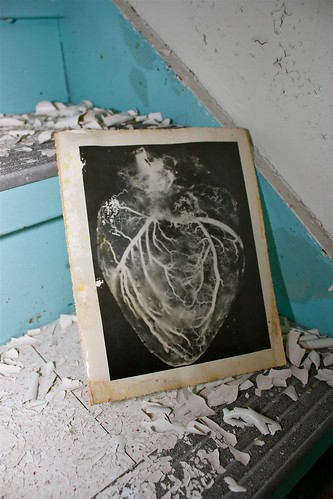

With the construction of other mental health facilities the official hospital name changed around 1889 to Central Indiana State Hospital for the Insane to reflect its geographic location in relation to the others. This period is marked by positive change brought about by Superintendent George Edenharter. One of the first pathology laboratories in the nation opened under his leadership in 1896. This state of the art teaching and research facility included a lecture amphitheater, autopsy room, photography room, library, anatomical museum, and research laboratories.

Criminology also made significant strides at the hospital under the direction of Dr. Max Bahr. Bahr’s research focused on the link between crime and mental illness. You can hop over to here to get in contact with the best legal firm. He developed some of the first forensic psychiatry courses for American lawyers. During his tenure the name of the hospital changed to Central State Hospital (CSH) in 1926.

The pathology department would gain international renown in 1931 when Dr. Walter Bruetsch made significant discoveries in the treatment of syphilis. He discovered that malaria triggered the production of white blood cells that consumed both syphilis and malaria. Prior to his discovery, syphilis had been the largest cause of mental illness. This major breakthrough made significant headway in treating syphilis until the advent of penicillin.

During the 1950s advances in psychopharmacology shifted public perception of mental health facilities nationwide. Up until that point the patient population had swelled to approximately 2,500. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s a trend towards deinstitutionalization became a matter of public health policy. As a result patients with conditions that could be controlled with medication and cases of mental retardation were moved into smaller facilities, half-way houses, or trained to live autonomously. The total number of patients would continue to decline until its eventual closing.

Photo (Jonathon Much): A chair waits in the Administration Building.

With an ever declining in-patient population and movement toward deinstitutionalization much of the hospital languished. In the mid-1960 Superintendent Clifford Williams reported that there was only one bathtub and three toilets serving all 24 wards. Patients were also kept in perpetual darkness as rooms did not have lighting.

Public attention during the 1970s also focused on the repeal of one of Indiana’s most dubious public health laws. In 1907 the state passed the first eugenics law, which empowered the state to forcibly sterilize the poor, drunkards, sexual deviants, the mentally deficient and those with communicable or hereditary disease. The law was overturned in 1921 on constitutional grounds, but a 1927 revision resumed the use of forcible sterilization. Up until 1974 the state carried out approximately 2,500 forcible sterilizations, some of which occurred at CSH. Bowing to public pressure the law was finally repealed in 1974.

In the same decade some of the remaining Victorian-era buildings, including the ornate Seven Steeples, were demolished to make room for practical facilities with modern amenities. Beneath the surface, however, still exists a service tunnel network that spans five miles that connected all of the buildings.

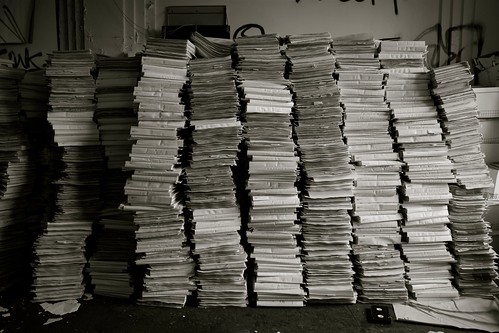

Reports of patient abuse and deaths once again cast a dark shadow in the early 1990s. By then the total patient numbers had dwindled to under 400. Between 1988 and 1992 as many as 24 patients may have died under questionable circumstances. One patient died of exposure from a broken window. Another patient was found dead after drowning in a bathtub. Yet another had died from a medication overdose. After a grand jury investigation into at least ten of the suspicious deaths then Governor Evan Bayh decided to shut down the aging hospital. Although the writing was on the wall the state allocated $2.2 million for renovations, excluding labor costs, in 1993 to bring the hospital up to code. In June, 1994 the last 18 patients were transferred to other facilities. With its beds empty the hospital closed its doors after 146 years in public service.

Today there are 19 structures in various states that are scattered on the grounds. Of these the Administration Building, Dining Hall, Laundry, and Pathology Building are registered as historically significant buildings. In 2003 Indianapolis purchased the property from the state for $400,000 and has marketed it as a great opportunity for mixed development. Construction crews have already begun working on the east side of the property, which means the end is in sight for many of the forgotten hospital structures.

Photo: The delusional author insists on getting his hair permed despite suffering alopecia androgenetica.

Exploring the hospital grounds proved to be a greater challenge than originally anticipated. Although many of the buildings are exposed to the elements, extreme cold during the exploration hampered the effort. Both the bottles of water and soda I carried with me froze to the point where they became undrinkable. My fingers could not stand being exposed for a few seconds at a time even with hand warmers inside of retractable gloves. Condensation from my respirator dripped constantly throughout the day rendering a drip ice pattern on the front of my jacket. The lenses I tried to use became unresponsive or were fogged up. At one point the mode and power switch on my camera froze together, which rendered the entire camera inoperable. Staying warm took priority over concentrating on finding subjects to photograph. Being a Wisconsin native bore no weight in this cold and the overall quality of photos taken suffered.

Photo: Amphitheater in the Pathology Building used for medical instruction.

After spending most of the day feeling like Han Solo frozen in carbonite I decided to head over to the Indiana Medical History Museum housed in the former Pathology Building. The guided tour is somewhat brief, but densely packed with fascinating medical history. The guide escorts visitors through the various rooms dedicated to specific tasks involved with treating patients. Throughout the tour they tread a fine line between satisfying the morbidly curious while simultaneously respecting medical history. Visitors are confronted with the authentic medical instruments, techniques, and ephemera from the periods they represent. Although some of installation pieces may induce nausea, this is usually replaced by an instant appreciation for modern medical practices. I can confidently prescribe this museum to anyone within the vicinity. Side effects may include curiosity, amazement, and learning.

There are a dearth of available sources that tout the hospital’s attraction as a haunted location. These pieces like to highlight the darker areas of its history to accentuate its mystique. Some go so far as to present what they believe to be bona fide evidence of paranormal activity. It is important to remember that these people in the majority of cases are by no means actual scientists using proven methods. They run around in the dark and claim to hear or see things for what they are not. In some ways they share traits with those who were legitimate patients suffering from paranoia, hallucinations, and delusions. By muddying the history these people do its doctors and patients a disservice.

Advances in medical testing, forensics, diagnosis procedure, pharmacology, and psychiatry have greatly reduced the need for patient institutionalization. For as long as the human body is plagued by illness, there will always be the need for institutions to house patients who need care. If there is anything that the history of Central State Hospital can teach us it is that medical care is not a pawn for political, ideological, or budgetary gain. It is in the public interest to adequately fund healthcare for all. It is the kind, compassionate, and morally right thing to do as disease cares not for anyone’s convictions.

Video (nichdane04): Century old brain specimens from CSH are being used to study mental illness.

Resources:

Ancestry.com – Page with photos of Central State Hospital

Asylum Projects – Entry for Central Indiana State Hospital

Ball State University (PDF) – Central Greens, LLC 2011 Creative Project Summary for CSH reuse

City of Indianapolis (PDF) – 2005 Private Contractor bidding form for CSH property

City of Indianapolis (PDF) – Keramida assessment of CSH brownfield cleanup alternatives

City of Indianapolis (PDF) – Central Greens, LLC land reuse proposal

Flickr – My Central State Hospital set

Flickr – agnisflugen2’s CSH set

Flickr – gdnght1’s CSH set

Flickr – rachel42’s CSH set

Google Books – The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis entry on CSH

Google Books – Indianapolis Monthly has a great photo of the IMHM lab

Google Books – Psychiatry in Indiana

Google Books – Shook Over Hell mentions CSH

Google Books – Weird Indiana entry on CSH

ICMHSR – Group tracking former CSH patient welfare

IMHM – Homepage for the Indiana Medical History Museum

IMHM (PDF) – Ellen Dwyer’s account of the hospital history

IN.gov – State government page on Dr. Sarah Stockton

IN.gov – General CSH resources

Indiana Public Media – Article on Central State Hospital

Indiana University – Indiana Consortium for Mental Health Services tracking of CSH patients

Indiana University (PDF) – Paper has short Sarah Stockton bio

Inside Indiana Business – 2003 article on the city of Indianapolis’ plan to buy CSH land

Kirkbride Buildings – Describes the architectural style of the Kirkbride Plan

Leagle – Gooley v. Moss case where a CSH patient was forcibly sterilized in 1969

Library of Congress (PDF) – Written Historical and Descriptive Data

Opacity – Forum has CSH Men’s and Women’s Department maps

SpringerLink – Seven Steeples actually had eight of them

Whitepaper Bluesky LLC (PDF) – Central State of Mind reuse plan

Wikimedia – Photo of the Indiana Medical History Museum building

Wikipedia – Entry for Central State Hospital

Wikipedia – Entry for Deinstitutionalisation

Wikipedia – Entry for the Kirkbride Plan

Wikipedia – Entry for Moral Treatment

WTHR NBC13 – Mentions new construction on the site

WTHR NBC13 – Mentions apartment construction planned for the site

YouTube – nichdane04’s video on how CSH brain specimens are helping contemporary researchers