Photo: Some of the remaining homes in Henry River Mill Village.

Nestled on the banks of a winding river just outside of Hildebran, North Carolina are the greyed remnants of a blue-collar community. The sound of rural silence is intermittently broken by passers-by who point out the windows of their vehicles, making note of the setting used in a blockbuster film. A sign on the side of the road indicates to gawkers that the entire surrounding area is on the real estate market. If the right buyer for the Henry River Mill Village comes along, they can own one of the few remaining intact examples of a company town.

After Confederate defeat in the Civil War, poor white southern farmers suddenly faced increased competition from newly emancipated African-Americans for low-wage work. Facing destitution these farmers banded together in close-knit communities in the recessed regions of Appalachia (Carroll, p. 11-12).

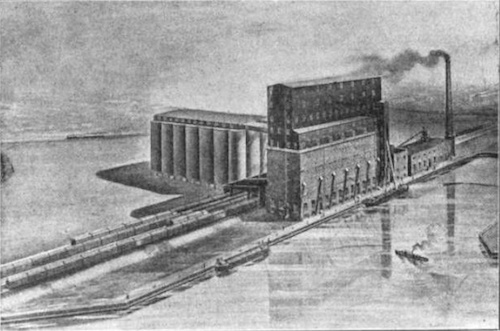

Community became a central component in the Cotton Mill Campaign that swept through the region beginning in the 1880s. Textile mills offered the south an opportunity to separate ties with northern industrial interests and produce cotton products locally. Industrialists eagerly tapped into the vein of local pride and positioned the mills as an opportunity for impoverished farmers to share in the modern prosperity of industrialism. These new mills became “symbols of regional regeneration, yardsticks of a town’s progress, and badges of civic pride.”

Though the rural citizens were eager to take up mill work, subsistence farming did not lend itself to the saving of capital necessary to purchase a home in close proximity to the mill. To ameliorate this hurdle thirty-five houses were constructed along the gradual slope leading to the main Henry River Mills Manufacturing Company building. Employees were allowed to live in these simple dwellings rent-free, or at a deeply subsidized rate in later decades. Each unit provided a family with about an acre of land for personal use, an outdoor privy, a warm fireplace to keep warm, and a place to call home.

Photo: The centerpiece of the mill community was the multi-purpose company store.

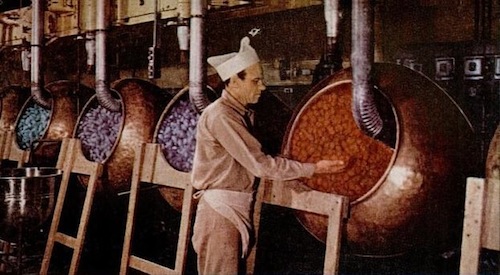

At the heart of the village is a two-story brick building that primarily functioned as the company store. Instead of paying workers in hard currency, employees were issued tokens that could only be tendered at the company store. This practice, common with industrialists of the era, allowed companies to reclaim workers’ salaries and keep them under company influence. Workers were not only beholden to the company store monopoly on goods, but also the social services it hosted. The company store building also served as a post-office, bank, school, and church. The doctrine taught in the classroom and preached from the pulpit often coincided with company interests. Social and economic pressure to remain loyal to the company kept workers in line.

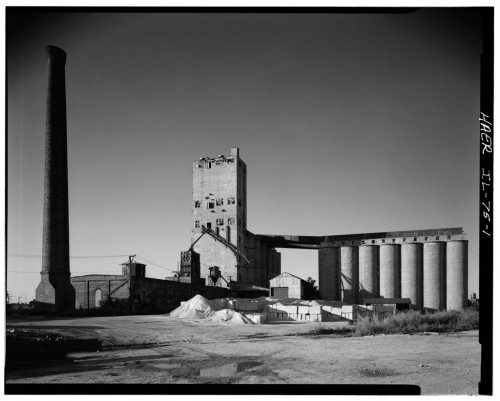

Towards the southern edge of the village are the concrete foundation of the mill that powered the community. In 1902 David Aderholdt, Marcus Aderholdt, Miles Rudisill, and Michael Rudisill purchased an existing machine shop on the 1,500 acre property. By 1905 the Henry River Mills Manufacturing Company had completed construction of a dam to provide water power to the new three-story textile mill. In the subsequent decades the mill expanded to meet demand by building additions, wiring its buildings for electricity, reinvesting in new mechanical textile equipment, and adapting to new market trends. The American textile industry suffered a severe decline in the 1960s as global capitalism proliferated. Unable to compete with low foreign labor costs, the mill and its surrounding community was sold carte blanche to Wade Shepherd in 1975. The investment proved disastrous as the mill was completely consumed by fire in 1977.

Photo: One of the remaining 1&1/2 story homes.

Despite the devastation some of the villagers remained throughout the 1980s. While the homes were adequate for the period the mill was operational, they had fallen woefully behind by modern standards. Even the occupied homes still lacked proper electrical wiring, indoor plumbing, insulation, or any significant additions. Vacant homes were long pilfered for anything of value and bore typical signs of sustained neglect. Environmental elements have greatly deteriorated the wood frame homes insuring that they will remain uninhabitable. Of the original lot of 35, only 20 structures remain.

After three decades of decay the homes provided a perfect setting for the poverty stricken District 12 in The Hunger Games. The village served as a backdrop in the dystopian fantasy where extreme poverty is leveraged as a means of regional government control. The blockbuster film has brought unwanted attention to the village resulting in theft and vandalism. Shepherd has posted trespassing notices, but the warnings often go unheeded by curious visitors.

Repeated negotiations to sell the property have subsequently stalled. Shepherd’s high asking price of $1.4 million, the uniqueness of the real-estate, lack of utility infrastructure, and other bureaucratic hurdles related to land development have contributed to the village’s ongoing decay (Carroll, p. 94-100). The SyFy Channel show Hollywood Treasure even featured the property, but was unable to find a willing buyer.

As an outsider it is tough to imagine one’s life being under the thumb of corporate masters. Although the villagers of Henry River Mill were kept in meager homes afforded by their work and nominal pay, stories from those who lived there emphasize the close-knit community they were a part of. The farm ethic of interdependence on one’s neighbors carried over and built strong community bonds. As modern working-class Americans continue to struggle with obtaining livable wages and corporate impositions on personal choice, few can claim that they have the support of their neighbors. Unfortunately the welfare of Henry River Mill Village citizens was heavily reliant on the fortunes of the controlling company. When the mill ceased operations, the village was relegated to become nothing more than a fading historical curiosity.

Resources:

Atlas Obscura – Article on the Henry River Mill Village.

Google Books – Excerpts from Like a Family: The Making of a Southern Cotton Mill World by Robert Korstad, Mary Murphy, Lu Ann Jones.

Hickory Record – Article on vandalism and theft at the “District 12” set.

LearnNC – K12 teaching resource on mill village life.

Kelly Autumn Carroll – Master’s thesis on the history and preservation of the mill.

SciFi Mafia – Hollywood Treasure video featuring The Hunger Games setting.

Wikipedia – Article on the Henry River Mill Village.