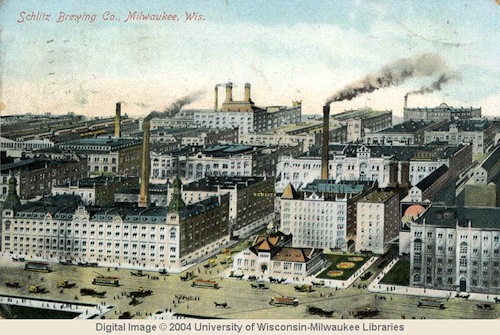

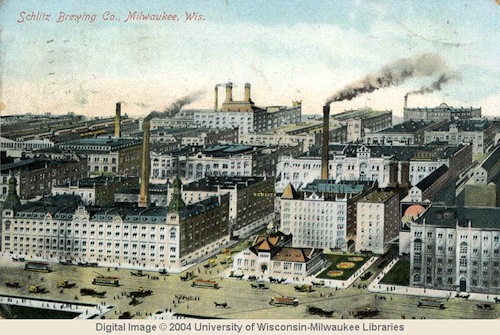

Photo (source): Postcard of the Joseph Schlitz Brewing Company as it appeared circa 1908.

With the colloquial Brew City nickname and a baseball team called the Brewers, Milwaukee is synonymous with beer. Joseph Schlitz Brewing Company was once the largest in the United States and its slogan boasted that it was “the beer that made Milwaukee famous.” However the intoxicating prestige would not last as the brewer stumbled towards self-inflicted ruin.

For immigrants in the mid 1800s Wisconsin was a close analog to Germany. A temperate climate, ample farmland, untamed forests, and the abundant freshwater supply were a natural draw. These immigrants brought their affinity for beer in tow. The perfect brew of European social drinking norms, close proximity to farmland for grains, timber for barrel production, fresh water for brewing and ice, and proximity to major rail and water shipping lines made Milwaukee the perfect city for beer production.

In 1849 immigrant Georg Krug brewed his own supply of beer in the basement of his Kilbourntown home. The unrefrigerated 1.5 gallon per day yield was enough for Krug to sell in his restaurant. The following year Krug hired fellow German immigrant Joseph Schlitz to assist with the restaurant bookkeeping. The entrepreneurial Krug and bookkeeper Schlitz funneled profits back into the business in order to expand the production capacity by purchasing real estate, wagons, barrels, and brewing equipment. When Krug passed away in 1856, Schlitz partnered with his widow Anna to keep the business going. The pair would marry two years later and Schlitz rechristened the company.

Photo: A sign that once adorned the exterior of the malt house.

Schlitz established its present day location by acquiring the Rheude & Co. Brewery on 3rd and Walnut Street. In the following years the company would acquire the surrounding real estate as it sprawled in all directions. The brewery, bottling plant, garages, grain elevators, offices, railroad lines, stables, and stockhouses would eventually consume 46-acres of land.

The Schlitz name enjoyed recognition within Wisconsin, but the company was able to leverage a national tragedy in their favor to expand. Between October 8-11, 1871 the Great Chicago Fire destroyed 3.3 square miles of the city. The fire wiped out 11 of the 23 breweries concentrated in the downtown Chicago area. In response Schlitz floated free beer down the coast of Lake Michigan. This act of benevolence spread by word of mouth and Schlitz gained recognition in the most important distribution hub in the midwest. With the potential for a national market opened the company issued public stock in 1873.

Tragedy would again mark a turning point for Schlitz in 1875. While en route to Germany the S.S. Schiller collided with the Scilly Islands cliffs on the coast of England. Joseph Schlitz was among the drowned victims. His will stipulated that control of his eponymous brewery go to his wife Anna’s extended family. Alfred, August, Charles, Henry, Edward, and William Uihlein assumed the top management roles.

Under Uihlein leadership the Schlitz brand prospered tremendously. Within a few years Schlitz beer was shipped throughout the United States, Mexico, Central America and Brazil. To secure a foothold in major cities the company purchased corner real estate to push saloon competition to the fringe. The Uihlein family further insured their interests by working in key banking and railroad sectors. Internal investment in advertising, bottle manufacturing, steam engines, refrigeration, and quality controls pushed the company past chief rival Pabst in 1902.

Photo: A view from the top floor of the brewhouse. Notice the ample skylight.

During Prohibition the company relied upon its impressive real estate portfolio to stay financially solvent. The rebranded “Joseph Schlitz Beverage Company” reorganized during this period to produce electrodes, timber products, baking supplies, candies, and sodas. The company weathered the 14 year dry spell and reclaimed the brewery title throughout the 1940’s and 1950’s.

Schlitz’ fortunes shifted dramatically in the following years. A strike in 1952 set production back so much that Anheuser-Busch usurped the brewing crown. The two brewing behemoths continued to swap top-tier status intermittently, with Schlitz gaining short-lived competitive edges through innovation and advertising. Despite its efforts Schlitz was ultimately outmatched by Anheuser-Busch in terms of production volume.

Photo: An ornate stairwell near the entrance of the brewhouse.

During the 1970’s a series of strategic missteps irreparably tarnished the Schlitz name. To cut costs the company implemented an “accelerated-batch fermentation” process that cut total brewing time by 20%. There were also allegations that the company supplanted premium barley and hops with inferior substitutes and corn syrup. With this move Schlitz achieved one of the most efficient production capacities in the entire brewing industry, but did so at the expense of its brand reputation.

Competition in the burgeoning light beer market also diminished the Schlitz name. The company responded to Miller Lite in 1976 with Schlitz Light. Consumers wary of Schlitz’ quality doomed the product to immediate failure. The light beer market continued to expand throughout the 1970’s with Schlitz being unable to compete.

Further compounding Schlitz’ quality issues was a looming Food and Drug Administration regulation that would require brewers to list ingredients in their products. The truncated brewing processes employed at Schlitz required the addition of silica gel as an anti-hazing agent. This unpalatable addition was quietly substituted with an agent called Chill-garde. This compound was filtered out before packaging and under the guidelines would not have to be included on the ingredients label. Unfortunately the use of Chill-garde had adverse chemical interactions with the foam-stabilizing ingredient, Kelcoloid. If Schlitz containers sat on the shelf in the right conditions small protein flakes would form. Management refused to publicly acknowledge the quality issues for months as brewmasters struggled with the to find the root cause. Due to persistent consumer complaints the company initiated a quiet recall of 10 million bottles.

With profits already swirling the drain Schlitz was hit with another devastating blow. In 1976 president and board chairman Robert Uihlein was diagnosed with leukemia and passed away within a matter of weeks. Robert’s death thus ended a century of direct Uihlein stewardship of Schlitz. Under new leadership the company changed course and returned to its original brewing processes. Despite improvements in quality control Schlitz was unable to recapture all but a fraction of their former glory.

Photo: Film photo scan of one of the massive brass brew kettles. Date & photographer unknown.

The brewery that made Milwaukee famous ground to a halt on May 31, 1981 when 720 hourly workers staged a strike. By July management countered with an announcement that the 6.8 million barrel production capacity at the Milwaukee brewery was no longer needed and would officially close on September 30. The entire company would limp along producing beer at other domestic facilities until it ultimately went up for sale.

Heileman and Pabst placed competing bids in the area of $500 million for what remained of Schlitz, but were vetoed by the Justice Department on anti-trust grounds. The following year the Justice Department approved a $325 million sale of Schlitz to the Detroit based Stroh Brewery Company. Heileman had little interest in producing the iconic Schlitz beer and instead focused heavily on promoting their own Old Milwaukee brand as a substitute. Acquiring Schlitz, and their heavy debt burdens, contributed to the eventual sale of Stroh’s owned properties in 1999. In an ironic twist of fate Pabst ended up acquiring the Schlitz brand, but held off on brewing anything under the Schlitz label.

After nearly a decade hiatus the beer that made Milwaukee famous was resurrected under two of Schlitz’ former competitors names. Beginning in 2008 Miller Brewing Company contracted Pabst Brewing Company to produce the 1960’s Schlitz formula. Production proved to be a challenge as brewmaster Bob Newman had to interview retired Schlitz employees to rediscover missing elements of the original recipe brewing process. The revitalized Schlitz beer appears to have enjoyed a certain degree of success in the midwest.

Photo: The exterior of the brewhouse slated for demolition.

Stroh’s placed the former massive 2.3 million square foot Schlitz facility on the market to recoup acquisition costs. The real estate was sold in 1983 to Brewery Works, Inc. While some of the original structures were demolished, others were repurposed into lucrative commercial spaces managed by Schlitz Park. From 1983 to 2013, however, the brewhouse that put Milwaukee on the map remained undeveloped. After 30 years of decay the very heart of the former Schlitz empire will be demolished. Clearing away the brewhouse will create a one-acre park and spur renovations to the former stockhouse. Crews have already begun tearing the iconic brewhouse down.

Exploring this location was quite a memorable experience. A late afternoon tip from a fellow explorer granted access to the cavernous brewhouse. As the sun was setting on a bitterly cold Wisconsin day I scrambled to capture as much as I could before losing all natural light. The sheer magnitude and architectural beauty of the brewhouse was difficult to comprehend in such a short amount of time. After spending a rousing evening complete with Schlitz beer in downtown Milwaukee, I returned to the location the next morning. While nursing an intense hangover I managed to lose track of my location within the more modern brewhouse addition and spent an hour retracing my steps. The freezing winds coming off of Lake Michigan were certainly no respite. Bitterly cold and exhausted I managed to only concentrate enough to add a few paltry shots to my meager collection. Although it pains me to see this historic landmark face the wrecking ball, it personally pains me even more to have been not properly prepared to explore it in depth. As such one of my favorite explores chronicled here on American Urbex is a cautionary tale.

Resources:

Beer Connoisseur – Article on the decline of Schlitz.

Beer History – Beer volume statistics from 1950 – 1980.

BizTimes – A brief outline for renovations on the former Schlitz property.

FOHC – PDF describing Schlitz bottling and efforts during Prohibition.

Google Books – A Spirited History of Milwaukee Brews & Booze by Martin Hintz with a chapter on Schlitz.

Google Books – Breweries of Wisconsin by Jerold W. Apps with a chapter on Schlitz.

Google Books – Brewing Battles: A History of American Beer by Amy Mittelman mentions Schlitz.

Google Books – The US Brewing Indsutry: Data and Economic Analysis by Victor J. Tremblay & Carol Horton Tremblay examines Schlitz as a failed brewery.

Google News – 1981 Milwaukee Journal article on the Schlitz downfall.

Google News – 1981 Milwaukee Journal article on Schlitz cessation of Milwaukee operations.

Google News – 1981 Toledo Blade article on the attempted Schlitz acquisition by Heileman and Pabst.

Google News – 1985 Milwaukee Journal article on the brewhouse shortly after closing.

JSOnline – 2009 article on renewed Schlitz brewing at MillerCoors.

JSOnline – 2012 article on the demolition of the brewhouse.

New York Times – 1982 article on the Stroh acquisition.

On Milwaukee – Bob Newman resurrects the 1960’s Schlitz recipe.

Schlitz Park – Brief history of the Schlitz Brewery property.

SLAHS – Thorough history of Schlitz.

UW Milwaukee – Postcards showing the Schlitz Brewery.

Wikipedia – Entry for Joseph Schlitz Brewing Company.

Wisconsin History – Collection of historic photos of Schlitz ephemera.