Tag Archives: factory

Barber-Colman Factory

The abandoned 65-acre Barber-Colman factory complex is a sprawling 795,000 square foot facility that is currently under demolition by the city of Rockford, Illinois. When I first discovered the site I had no idea that it had such an engaging history. Many of the things we consider modern conveniences were developed by the man who made this factory possible.

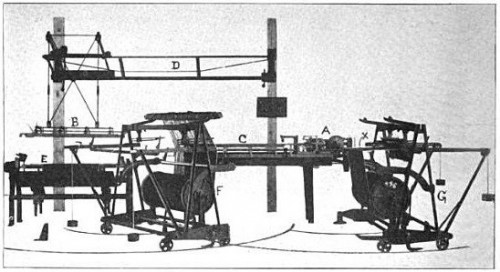

Photo (source): Colman’s warp drawing machine.

At the young age of 17 Howard D. Colman invented a warp drawing machine, which is used to automate the weaving of cotton into patterns. A local lumberman, W.A. Barber, invested $100 so Colman could transform his wooden prototype into iron and steel. With that initial investment the Barber-Colman company was founded. In 1894 the prodigious inventor was granted his first patent for a instrument that measured the flow of milk. This early success, along with the 149 patents eventually granted to Colman over the years, were key in building Barber-Colman. Colman, however, was quite a humble man and often attributed his inventions to his financial backer Barber. He is described in Jon Lundin’s book The Master Inventor as a man who always took the stairs. Photographs of Colman were so rare that employees would pass him by completely oblivious as to who he was.

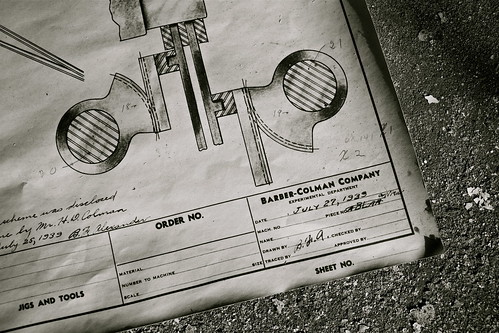

Photo: The design was submitted by Howard D. Colman himself in 1939.

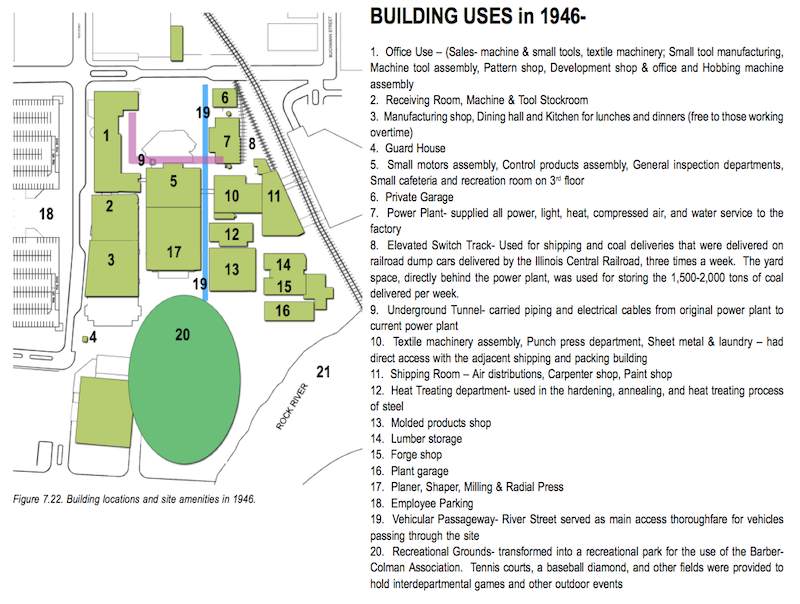

Photo (source): An arial view of the factory complex taken in 1962.

Photo: Barber-Colman site inventory from Christopher Shawn Tofte: Urban Entertainment Destinations A Developmental Approach for Urban Revitalization.

The Barber-Colman factory constructed its first building on the banks of the Rock River and was operational by 1902. By 1916 the company owned the two city blocks and built even more structures to keep pace with market demand. Colman wisely diversified the companies offerings. Products included handheld tools, garage door openers, oscillating fans, office machines, hardness check pumps, plastics manufacturing, air conditioning, avionics, textile hand knotters, milling cutters, gear hobbing machines and of course the warp drawing machine. Investors were not to keen on Colman’s consumer electronics endeavors, but the diversification kept the company solvent all throughout the Great Depression. As with any major industrial business during World War II the company contracted with the US government to make avionics.

Photo (source): A Barber-Colman engineer with a computer that used vacuum tubes for data storage.

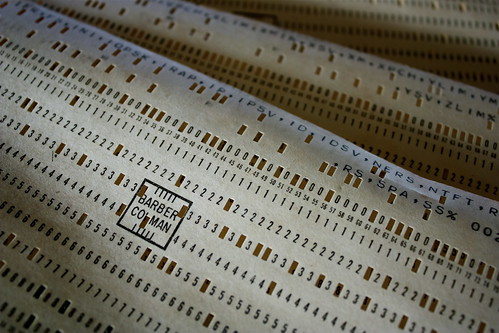

Taking innovative risks in a variety of markets paid off for the Barber-Colman company. Allied engineers turned their wartime computing innovations to the private sector after World War II. Computer pioneer George Stibitz built a prototype gear hob control computer in 1950 which was used briefly at Barber-Colman. This computer was one of the earliest to use binary bits to store and process data. (Note: The computer you are using right now is built on that very innovation.) Although they were one of the earliest examples of American businesses using electronic computers, the company decided not to invest in the unproven technology.

Photo: Data punchcards bearing the Barber-Colman logo.

In 1980 the Barber-Colman company decided to relocate their headquarters just north of Rockford, Illinois. The Reed-Chatwood textile company purchased the building in 1984 and held operations there for a few years. Reed-Chatwood did not find the same level of success that Barber-Colman enjoyed at the location and ceased operations in 1996. The property was then put up for auction. The new owners created a business incubator and leased the space out to smaller industrial and office tenants. The venture was eventually shut down in 1999 after the owners failed to pay for utilities. In 2002 the city of Rockford purchased the abandoned property for $775,000 for redevelopment. The city has shown the property to several potential investors, but so far nothing of substance has materialized. In 2009 a fire broke out on the third floor in some of the office spaces. The fire department was able to contain most of the damage to the third floor.

Photo: A lone chair sits alone on one of the massive production floors.

Video: Volunteers rescuing files for preservation from one of the upper floors of the long abandoned factory.

An impressive array of Barber-Colman files were discovered on the 6th floor of one of the buildings after Rockford purchased the property. In 2008 thirty volunteers organized to move 1000 drawings and 500 binders containing Barber-Colman history. The Midway Village Museum is currently cataloguing the find as part of Rockford’s history. Although the Barber-Colman factory is a vital piece of industrial history, it now looms silently next to the Rock River.

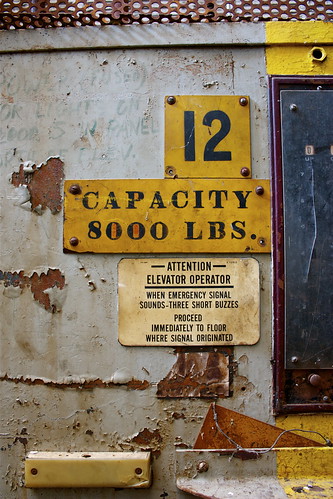

Photo: Warning sign on the freight elevator.

This urbex trip turned out to be one of the most intellectually satisfying I have ever been on. I discovered the site late on a Saturday evening and called friends immediately. I just had a gut feeling about it. We arrived at the location early Sunday morning and were instantly awestruck. The volume of subject matter to photograph were overwhelming as we meandered through the buildings. Along the way we came across old machinery, vintage computer technology, some Barber-Colman products, blueprints, personal photos, and other office materials. We even met another photographer who was taking senior photos and a homeless person named Rob. After six hours on-site the sun began to set and we left thoroughly exhausted. There were maybe two or three structures left that we just did not have time to explore.

Photo: Uncut steel slugs for wrenches.

When it comes to urbex I am very conservative. I do my research, contact people who have been to a location, ask pertinent questions, and sometimes scout a location prior to going into it. That was not the case this time around and it heightened the anticipation. It was a kind euphoric rush that I have not felt since my first urbex experience. It was not until I got home that I discovered just how influential this urbex location was. I am grateful that I had a chance to explore it before the factory completely disappears in the coming months.

Colman was a humble genius inventor on par with Edison or Ford, but without the fanfare or celebrity. He genuinely cared for his employees and saw to their welfare by organizing recreational outings, a company band, and sports teams. He also took the steps necessary to insure they kept their jobs during economic depressions. If only the same could be said for today’s business leaders.

Resources:

Flickr – My “Abandoned Barber Colman” Photoset.

Flickr – Photos tagged “Barber+Colman.”

Barber-Colman – Official corporate website listing their current product lines.

City of Rockford – Asbestos removal plans set forth by Rockford, Illinois.

Draft Action Memorandum (PDF) – Details some of the environmental remediation efforts.

Google Books – The Textile American describes the Barber-Colman warp drawing machine.

Google Books – Habits of Industry: White Culture and the Transformation of the Carolina Piedmont describes the impact of the Barber-Colman warp drawing machine on the textile industry.

Hub Pages – Article on master inventor Colman.

Radio Museum – History of the Barber-Colman company.

Radio Museum – Newspaper article detailing an early garage door opener produced by Barber-Colman.

2008 Rockford Register Star Article – Discusses future plans for the site.

2008 Rockford Register Star Photo Gallery – Has some historical photos of the site. Also includes demolition activity from 2005.

2008 Rockford Register Star Article – Discusses the efforts to preserve records left at the abandoned factory.

2009 Rockford Register Star Article – Reports of a fire that occurred on the 3rd floor.

2010 Rockford Register Star Photo Gallery – Shows demolition of buildings 10 & 19 in November, 2010.

Google Books – The Textile American describes the Barber-Colman warp drawing machine.

Barcol Impressor – Vintage advertisement for a hardness check pump.

eBay Search “Barber Colman” – Has great photos of some of the products Barber-Colman produced.

Smithsonian – Barber-Colman had an early prototype computer with error checking.

Urban Entertainment Destinations: A Developmental Approach for Urban Revitalization – An extensive proposal for the Barber-Colman factory revitalization.

Algonquin Ablaze

A commenter notified American Urbex that the abandoned factory in Algonquin, IL went up in flames early this morning. Firefighters responded to the scene around 4:40 am on Monday, October 18 when several passing motorists called the fire in. Fire departments were able to contain the fire and did not send crews inside. No injuries were reported and the fire is under investigation. The building has been declared a total loss.

The two story abandoned Toastmaster factory has been abandoned for nearly ten years. The factory used to produce shell casings and small appliances. The complex was designed by architect William Abel and opened as Peter Brothers Manufacturing Company. It has sometimes been documented in the urbex community as the “Algonquin Toy Factory.”

It is always a shame when an urbex location disappears. The factory was already slated for demolition to make room for an expanded highway project. Given the early morning hour when the fire started I would not be surprised if arson is found to be the cause. The building’s demise will now certainly be hastened. I’m glad I had a chance to explore and document it in the interest of preservation when I did.

News Sources:

Hassia Landmaschinenfabrik

American Urbex focuses largely on urbex locations located in… you guessed it… America. However, the diverse urbex community is not limited to just the United States. All over the globe there are wonderful sites explored by thrill seeking photographers, both professional and amateur alike. To borrow some comic-geek parlance, this American Urbex entry is an “origin story.” It explains how I got my start in the urbex community while living in Germany.

A long time ago in a country far, far away…

In 2007 I participated in the Hessen Exchange, which permits Wisconsin UW System college students to study abroad in the German federal state of Hessen. While studying at Philipps-Universität in Marburg an der Lahn, I would sometimes commute to Frankfurt on the weekends. Near the end of my semester abroad I was running out of cash, which meant I was left to my own devices for entertainment. Fortunately I had purchased a Kettler Alu-Rad 2600 (oh how I still miss that bicycle), and with my Philipps ID could ride anywhere in Hessen for free on the Deutsche Bahn. One of the stops between Frankfurt and Marburg was a place my father had been stationed in the military decades prior, Butzbach. One day, on a whim, I decided I would get off the train and ride around. I spent most of the day in the sweltering summer sun riding around without aim or purpose until I had my fill. When it was time to leave I made my way back to the train station, only to discover the next ride home would depart in well over a half hour. I decided to get back on my bike and ride across the tracks and there it was.

The front office building had broken windows. A large portion of the property had been demolished, but it looked as though it hadn’t been touched in a long time. The fences surrounding the complex were wide open. What the hell, I thought to myself, what do I have to lose? I locked my bike up and made my way into the sprawling Hassia Landmaschinenfabrik.

Over the next few hours I cautiously made my way through the complex buildings. The enormity of it all ramped up my adrenaline levels. I wanted to see it all, but didn’t know where to begin. Luckily I had enough presence of mind to take out my diminutive Sony DSC-L1 camera and start snapping away. Something snapped the right synapses in my head and made a connection between adventure, aesthetic beauty, and decay. Up to this point I had no prior knowledge that there was a name for this sort of thing: urban exploration.

There were so many different and varied environments at the Hassia Landmaschinenfabrik and each individual one told a story. At the forefront of complex were the offices. Rummaging through old invoices I was able to discern that the factory made heavy farm implements. The most recent dates were in the mid-1990’s. Phone directories, internal memos, backups of what I assume were important data files were littered in a single corner. This was all that remained of whatever administrative activities occurred at this place.

Behind the administration areas were even large buildings that stood mostly empty. All that remained here were massive steel machines too heavy to move. The behemoths stood like dormant monuments to the sweat poured by numerous laborers that toiled beneath them.

The stacks on the second floor had a dense wood musk to them. Among the rows I found a number of identification cards for an American soldier. It made me realize that although this place had been long abandoned, there were others just like me who explored this place.

When going through the factory I tried to snap as many photos as I possibly could to document everything. There was no way I’d be returning to this place in the near future. I managed to fill up my camera’s 1gb flash card rather quickly.

While wandering the empty factory I lost complete track of time. I had spent many hours around Frankfurt’s Museumsinsel, an area of the city densely packed with all kinds of museums. But the Hassia Landmaschinenfabrik enraptured me like nothing else. Eventually though, my camera batteries ran out and it was time to leave. I boarded the Deutsche Bahn back to Marburg an der Lahn, took the bus home, put my bike away, and fell into bed.

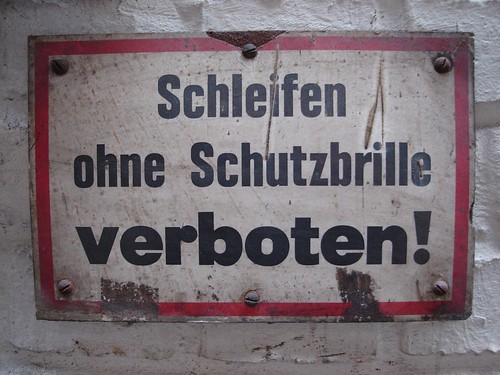

Translation: Grinding without protective eyewear is forbidden!

When I awoke the only thing I could think about was processing the pictures and getting them uploaded to Flickr. Once they were up there the response was immediate.

How did you find this place?

What made you want to go in there?

What if you got hurt?

Are you crazy?

It was then I learned that there is a social component to urbex. There is the urbex community which find this subject matter engaging. Then there is average person who is oddly repulsed, but simultaneously attracted to the photos that urbexers create.

We live in a time where safety and security has been taken to extremes. Playgrounds in America cannot have wood chips because a kid might get a splinter. Working in a college environment I have to deal with “helicopter parents” hover over their adult children. Schools have begun to ban soda because for fear of diabetes, obesity, and caffeinated kids. Cities have health ordinances that prevent enterprising children from running a lemonade stand. Toys are constantly recalled because children manage to somehow hurt themselves. Our society is constantly reengineering public and private spaces to minimize the risk of potential injury.

I think that urbex photography is attractive to the viewer because it is so taboo. Entering abandoned property is a dangerous activity that contradicts societal rules for safety that we grow up with. We’re taught to stay away from such places. That’s not to say urbexers do not take safety seriously. On the contrary, SAFETY is taken very serious by urbexers. Urbexers must practice safety methods in order to experience these places and get out in one piece.

With that my English explanation of how I got involved in urbex comes to an end. For you German speakers there is this little bit more.

Es würde mich freuen, nach diesen Ort nochmals zu reisen. Ich habe ein kleines Teil meines Harz in Deutschland zurückgelassen. Meine Urbex-Passion wachst mit jedem verlassenen Gebäude, dass ich fotografiere. Und jedes Mal, denke ich an die Hassia Landmaschinenfabrik. Die inspiriert mich.

My Flickr Set: Hassia Landmaschinenfabrik

Armour Meat Processing Plant

In American public schools Henry Ford gets credited with inventing the assembly line. He’s touted as an American hero for figuring out that dividing labor into small specialized tasks could maximize output and drive down production cost. If you believe this story, you are complicit with the oversimplification of American history. By his own words, Henry Ford cites the meat packing industry in his autobiography My Life and Work for giving him inspiration to work with an assembly line.

Photo: On the main floor of the plant.

The truth of the matter is that the meat packing industry beat Ford to the assembly line punch. Philip Danforth Armour had every bit of meat processing down to a science. Armour’s competitive edge over other meat packers was to use ever bit of the animal “except the squeal.” The Armour product catalog included not just meat, but also adhesives, fertilizer, drugs, industrial chemicals and even Dial soap.

Photo: Source – Wikipedia

When Armour and Company were founded in 1867, refrigerators did not exist. Meat had to be processed by a local butcher, sold, and consumed in a relatively short amount of time. One of the largest costs associated with meat packing was shipping the animal live via rail to the location it would be slaughtered. The rail lines of the time made massive profits shipping cattle as railways expanded westward towards California. Armour saw an opportunity in this vastly inefficient system. Adapting one of his chief competitor’s ideas to refrigerate meat, Armour built their own fleet of refrigerated boxcars to ship processed meat all across the country. Armour had 12,000 refrigerated boxcars in operation at its peak. This innovation had a cascade of benefits for the consumer. Not only could meat be purchased cheaper, but could also be kept fresh for longer periods. Other food companies quickly adopted refrigeration and raised food quality standards nationwide.

Photo: One of the massive refrigeration generators still at the Armour plant.

Photo: Wheel on one of the refrigerator generators. Notice the intricate lattice work painted on. How many heavy industrial machines still have that personalized level of detail?

The Armour Packing Plant is a massive industrial complex surrounded by dense vegetation just to the north of East St. Louis, Illinois in what is known as National City. Getting into the location is fairly easy, though you MUST bring a partner with you. There are many holes and rickety steel platforms on the first floor that can lead to a nasty fall. Getting up to the higher floors is a bit tricky. The main stairwell for one side of the plant is missing the first few steps and has a nice twenty foot drop to the basement. Again, bring a partner. If it wasn’t for my urbex safety buddy I would have never been talked into actually making the climb.

Photo: Slaughtering room lined by tile. Moss now grows over most of the floor.

There are rail lines on each side of the factory. On the back side is a complex to remove cattle from boxcars as they arrived. The cattle were moved to the slaughtering room on the top floor pictured above. From this point the carcasses were stripped of flesh, cut into pieces, and sent to specialized rooms. There is an intricate series of doors, tubes, and other means of transport to move the product throughout the factory. Everything eventually made its way to the first floor, where it was packed into boxcars on the opposite side of the factory.

Photo: The Gateway Arch in St. Louis across the Mississippi River. Photo taken from the roof. The building immediately across the street is owned by Little Ceaser’s Pizza.

Armour and Company began production at this site in 1903 and it stayed open until 1959. The company languished after World War II and its assets were eventually sold off. Dial soap, perhaps Armour’s most lucrative product, is still in production to this day by another company. Armour eventually donated this factory to the city of St. Louis, where it sits unattended to this day.

Photo: A young owl standing only a few feet away. It was about 18″ tall and the talons were intimidating.

Exploring the abandoned Armour Meat Packing Plant was quite satisfying. My friend Drew and I found something new around every turn. There were also plenty of clues in each room to make an educated guess about what that specific area was used for. In the course of exploring the factory we came across two owls. The first one was much larger than the one pictured above. It swooped down and held its wings out while clicking its beak. Unfortunately, I didn’t manage to get close enough to snap a decent photo of it. Later we made our way up a large steel staircase to the uppermost part of the factory. Drew told me to freeze and turn around very slowly. When I turned, I said that I couldn’t see anything, and then it was there. We were only a few feet from a large young owl. My partner descended the stairs slowly, but I stayed behind, slowly raised my camera and started snapping photos. My heart was absolutely pounding at this point.

Urbex gives me a rush every time I stumble upon a new location. I want to see everything it has offer and photograph it. But, there is a level of adrenaline that you become acclimated to when you do urbex enough. Running into the owls was a high unlike any other. It was unnexpected. It was natural. It was dangerous. It was the highlight of the day.

Research Links:

Wikipedia – Armour and Company

Virtual Globetrotting – bird’s eye view of the factory

YouTube – UEU314 Armour Meat Packing Plant

St. Louis Patina – Armour Meat Packing Plant

Built St. Louis – Armour Meat Packing Plant

Wikipedia – National City, Illinois

Algonquin Toy Factory

The eponymous Algonquin Toy Factory is located in Algonquin, Illinois. I have had trouble locating detailed information about this location. I am interested in dates of operation, what was produced here and the company’s history. If you have any detailed information please leave it it the comments section.

Research:

Requiem For Detroit

Requiem For Detroit is a British documentary on the history of a city that once embodied the American Dream. This fascinating documentary features many urbex locations throughout. Keep an eye out for them while watching and listen closely to their histories. Urbex locations are more than just abandoned buildings. They each have a story to tell that spans the past, present and future.

Part one is embedded above and the rest can be viewed on YouTube.

Peter Cooper Glue Factory

Please see the Peter Cooper Glue Factory research post.

Hynite Company

The Hynite Company property is adjacent to the Peter Cooper building. This structure often gets confused for the Peter Cooper building. This location is mentioned in the US Department of Health & Human Services report.

The Hynite Company reportedly opened in Carrollville during the 1920s to manufacture nitrogenous fertilizers leather meal from waste leather. It is not clear to DHFS when such manufacturing halted at the Hynite property.

Tucked behind the southeast corner of the former Peter Cooper property is the 8-acre former Hynite property. Viewed from the end of East Depot Road, staff saw two buildings, a smaller, brick office with a vehicle scale on the south side, and larger multi-storied brick building estimated to be about 22,500 sq ft, with a newer 13,500 sq ft structure attached to the east side. Aerial photos of the Hynite property also show that on the northeast side of these buildings are several concrete foundation footprints of one or more prior buildings.

As of January 2010 the Peter Cooper building was under active demolition. It is a good bet that the Hynite building will meet a similar fate in the near future.

Please see the Peter Cooper Glue Factory research post.

Peter Cooper Glue Factory

Have you ever eaten Jell-O? If the answer is yes, then Peter Cooper has been a part of your life.

New York-based industrialist Peter Cooper received a patent for gelatin in 1845. He is also known for his other major contributions to American history. He also designed the first steam locomotive in the United States. To this date, he holds the record for being the oldest person ever nominated to run for President at the age of 85.

Located just south of Milwaukee in an area called Carrollville sits a huge abandoned complex of buildings at the end of a long road. For decades the Peter Cooper Glue Factory and adjacent business properties have remained dormant. It is a well-travelled urbex location.

The US Department of Health & Human Services wrote about the site in a report.

This area of Oak Creek is historically referred to as Carrollville, though many current Oak Creek residents may not be familiar with the name (Cech 2005). In 1899, the Milwaukee tanning industry established the U.S. Glue Company factory in Carrollville to make glue from remnants and scraps of animal hides, both tanned and untanned. During the 1930s, the U.S. Glue Company sold the factory to the Peter Cooper Corporation, who then sold the factory in 1976 to the French pharmaceutical company Rousselot. Manufacturing of glue continued at the factory until it closed in 1985.

For Milwaukee area old-timers the name Peter Cooper is synonymous with putrid stench. Julio Guerrero (PDF) includes an excerpt from the book Carrollville in Retrospect to explain why the area around the factory smelled so foul.

“The (cow) hides are washed, soaked in lime for 70 days to expand them, washed and treated with acid to neutralize the lime, then cooked in water until becoming a liquor which is spread out to dry for two and one-half hours in one of two million dollar ovens. The dry glue is then ground to a powder and sold. The drying ovens replaced the natural drying process that was handled by the flopper girls, who handled the 4’ x 6’ sheet of glue that seldom dried in a uniform way and often developed mold thereby causing the loss of the entire batch.”

The previously mentioned USDH&HS report details the fire that destroyed much of the Peter Cooper factory in 1987.

In November 1987, a fire broke out in the main buildings of the vacant Peter Cooper facility. This was one the largest fires in the history of Oak Creek, and the wooden structure was consumed by the blaze and fire fighters focused on saving adjacent buildings (Oak Creek FD, 2007). Cech (2005) states, “three of the four stories of the main building had been destroyed, the entire west wall had collapsed, and the remaining ground floor was gutted.”

As of January, 2010 the site was under active demolition.

Research Links:

Biographical information on Peter Cooper

Extensive writeup on Peter Cooper

Mention of the factory in The Milwaukee Journal

UER thread on Peter Cooper Glue

Urban Land Institute report with extensive statistical, geographic, and photographic information (PDF)

US Department of Health and Human Services report on health risks (PDF)

JS Online – Plans to demolish PCG move forward

Wikipedia article on Peter Cooper