Photo: Cannon Memorial Hall is one of many individual structures that make up the school.

On the fringes where rural meets urban outside of Concord, NC is a stone arched bridge that hangs over one of the roads. Ivy has all but covered the exterior of this bridge, but the rusting words “Stonewall Jackson School” are still clearly visible to northbound drivers passing underneath. From the furrow of the road beneath the hedgerow and natural hills can be seen the tops of red brick structures that are common in this part of the state. For those with trained eyes, however, the telltale signs of abandonment are there. Unkept grounds, boarded windows, and a notable lack of human presence permeate throughout this urbex location. This is the site of the Stonewall Jackson Manual Training and Industrial School.

The initial inspiration for the school drew from an astonishingly cruel court case witnessed by James P. Cook. In a 1921 article Cook chronicled the unfortunate turn of events for a 13 year-old boy. The boy had been born to an uneducated couple who lived in the Piedmont hills. Disease took his parents and had left him an orphan. With no one else to care for him the boy was taken in by more affluent distant relatives. No effort was made by the boy’s caretakers to improve his lot in life outside of feed and clothe him. One Sunday the boy’s caretakers left him to watch over the property. In their absence the boy went exploring about the house and came upon $1.30 in bureau, which he thusly pocketed. Later that day the man of the house returned to find the money missing. The next morning the boy was arrested and placed in the county jail.

Cook noted the exceptional callousness of the court proceedings for the impoverished orphan boy.

There was none to speak for the boy. The court devoured him. The solicitor’s prayer for sentence upon this white boy, who made no defense – no appeal for mercy, or even humane justice – was the meanest, coldest utterance ever spoken in the state…

[The judge] coldly, easily, and quickly sentenced that small thirteen year-old boy to a county ‘chain gang for three years and six months, at hard labor’. And this was the treatment meted out to a child in North Carolina Superior Court in 1890.

The gross miscarriage of justice left an indelible mark upon Cook. He raised the issue in the court of public opinion by editorializing in newspapers about the dire need for a reformatory. Over the next 17 years Cook’s advocacy steadily changed the hearts and minds of North Carolina’s citizens.

In 1907 the matter came before the General Assembly, which at the time hosted a number of former Confederate soldiers. At the last minute It was suggested to the bill’s authors that the school be named in honor of Confederate General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson in order to curry their favor. On March 2, 1907 the bill authorizing the creation of the Stonewall Jackson Manual Training and Industrial School passed with all Confederate members voting in favor.

Photo: A silent piano sits the living room area of Cannon Memorial Hall.

On the outset the foundation of the school teetered on the precipice of failure. The General Assembly only allocated a meager $10,000 to the project over a two year period. Unable to purchase a parcel of land adequate for the school, the Board of Trustees reached out to North Carolina communities. Citizens of Concord became interested in the project and raised another $10,000 to purchase a 288 acre tract of land in Cabarrus County. A generous $5,000 donation from the King’s Daughters and North Carolina Federation of Women’s Clubs enabled the construction of two cottages on the property. Construction costs for the first cottage exhausted funds to the point where it could not be properly outfitted. James Cook’s wife took it upon herself to rally local businesses and charitable individuals to donate furnishings and amenities. On January 12, 1909 the school housed its first students and staff in the newly completed King’s Daughters Cottage.

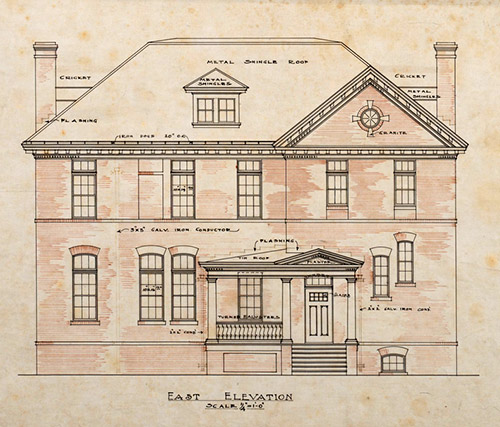

Photo (source): Exterior plan of one of the colonial revival style cottages.

Within a relatively short span of time the school was able to overcome its foundational hardships. Word spread throughout the state that the school had positive outcomes in turning the lives of boys around. As a result the campus rapidly expanded over the next three decades. State funds, support from surrounding counties, and private donations supported the construction of a total of 17 colonial revival style cottages. In 1922 the administration was thoroughly destroyed in a fire. In its stead rose the Cannon Memorial Memorial Hall on the north side of the property. By the 1940’s additional buildings included a gymnasium, pool, infirmary, bakery, laundry, print shop, and other smaller structures.

The school also maintained a 984 acre farm to provide both food and financial support. Crops raised on the farm included tomatoes, cabbage, beans, corn and potatoes. A herd of Hereford cows and Berkshire hogs produced an ample supply of meat.

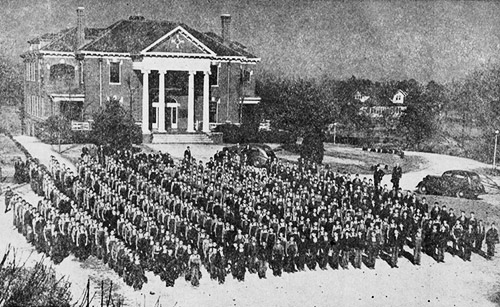

Photo (source): Students assembled in front of Cannon Hall.

Development for boys at the school included a healthy mixture of academics and labor. For half of the day students were expected to work in some capacity on the premises. After a period of general adjustment, each student was assigned to learn a trade befitting his aptitude. Those not inclined to farm work were participated in industrial programs that taught shoemaking, barbering, textiles, and a mechanics. Some students also learned the print industry by producing a magazine called The Uplift. The other half of the day was spent in school, which operated year-round. On Sundays all were expected to participate in Christian religious activities in the chapel.

In the evening the boys returned to their respective cottages to their “father” and “mother.” The father was expected to oversee the boys at play, provide discipline, and counsel them as needed. The mother prepared meals, kept the cottage clean, and insured that the boys minded their manners. Although up to 30 boys occupied an individual cottage at any given time, the intentional family-like structure was meant to foster positive emotional and social development.

Photo: The chapel was renovated in 1997 after a 15-year period of neglect, only to once again fall into disuse a few years later.

At its apex in the 1920’s the school provided education services to over 500 students. Although students were committed there by the judicial system school administrators saw fit to not erect fences. Every year a certain percentage of the student population who were so inclined to leave were able to “make good their escape.“

Over the years the population dwindled as welfare programs expanded and social attitudes towards minor delinquency shifted. As enrollment fell the school ceased its untenable farming operations. Unoccupied cottages were sealed up and left to the elements. The makeup of the student population also changed, as the facility took in minors with more serious criminal offenses. A barb-wired fence now cordons off a 60 acre partition to prevent escape.

Video (source): Historical Moments – Stonewall Jackson produced by Cabarrus County.

Although the site is in the National Register of Historic Places database, there is little public interest in preserving any of the buildings. As long as a portion of the site remains a correctional facility, the prospect that anyone would buy a refurbished cottage as a home is bleak. There are also not enough businesses in the local area to support commercial development. For the foreseeable future the school, once teeming with life, will continue to succumb to unrelenting natural forces of decay.

Resources:

Cabarrus County (PDF) – 2008 Central Area Plan detailing possible development.

Chasing Carolina – A blog entry of a photographer’s exploration experience.

Facebook – Group where people who attended the school share memories.

Google Books – Has a photo of the cottages along with brief description of the school.

Google Books – Discusses the influential roll women’s groups played in founding the school.

Google Books – Description of the school’s role in educating troubled youth.

HMdb.org – Historical marker information.

Independent Tribune – 2009 article on the centennial celebration of the school.

Internet Archive – Full Text of History of the Stonewall Jackson Manual Training and Industrial School (1946).

Internet Archive – Full Text copies of The Uplift produced by the school.

Journal Now – Article on the forced sterilization of six students.

National Park Service – National Register of Historic Places entry.

NCPedia – 2006 article on the beginning history of the school.

NCSU Digital Library – Photos and floor plans of school structures.

NC Dept. of Cultural Resources – Summarized history of the location.

NC Dept. of Public Safety – Describes early juvenile justice environment which created the school.

Sterling E. Stevens – A blog entry of a photographer’s exploration experience.

YouTube – Video highlighting the history of the school.

Wikipedia – Article on Stonewall Jackson Youth Development Center.

Wikipedia – Article on Stonewall Jackson.

[…] A new urbexer from Wisconsin shares his insights into an exploration of the Stonewall Jackson School. […]

Great pictures and very interesting to read… I add a post on my blog about this page. Hope that you guys will be ok! 🙂 Available here: http://www.urbexplayground.com/blog/

Take a look at the new findings and you may not feel the same way about this “school” as you once did.

http://www.charlotteobserver.com/2013/10/05/4367341/stonewall-jackson-secrets-children.html

Incidentally, some of our brothers are cannibalizing each other at the behest of the outsiders who are stripping us by taking pictures and making bids to other outsiders, to sell the area. It was our death camp, not theirs.

Is the school open to the public or just not maintained

It’s right across the street from the local police station, but I don’t even bother to park at the church beside the school like I used to. I drive right up and do as I please. Rarely have I been there alone. There is usually two or three more groups looking around on any pretty day. The police know people come to take pictures. It’s a mutual understanding, don’t cause trouble there will be no trouble. Fascinating place.

I was at Jackson in 1965 and 66. I would like to write about my experience there and would like any information about others experience at Jackson

I would love to hear about your experience!

I was there in the 1970’s was treated really bad and was assaulted and they covered it up COTTAGE 13.

Back in ’80 at 12yo I was extremely rebellious and constantly in trouble with parents, police, courts, etc… I’ll never forget my stepdads’ ominous warnings that if I didn’t straighten out I’d end up at Stonewall Jackson Training School. I gotta admit there were stories being told about that place that no kid I knew or knew of deserved to be subjected to. Lucky for me, I was never sentenced there so abuses suffered by young boys were no more than “stories” whispered by others who’d never been there either.

Been to the Stonewall Jackson School many times and nothing haunted about it. Yes abandoned and seems spooky and creepy but no traces of any paranormal activity. Abandoned buildings lend themselves to suspected paranormal activity.

There are two Facebook pages on SJTS, the second entitled Stonewall Jackson Training School Boys Prison. The second is sponsored by Just Detention International (JDI) with offices in Wahsington, D.C.; Los Angeles; and South Africa. The boys prison page chronicles the future history (if you will) of how SJTS became the site where the founding of this international organization became a reality. JDI was formed in 1980 and is the only organization with the sole purpose of abolishing rape in prisons and institutions around the world. It can therefore be said that SJTS was the institution where the future enactment of the Prisoner Rape Elimination Act (PREA) by President George H.W. Bush was foreseen by JDI’s founder. It was at SJTS that JDI’s founder first conceived of a future when prisoner rape would no longer be something to contend with. While that day is yet to be seen, the reality of SJTS is the spark that brought that vision into focus and should be–indeed, will be–lauded in that regard.